Radical Imagination & Autonomous Design

As designers, can we come together to create new ways of communicating and build truly autonomous zones? Spaces where people feel welcome to gather, share ideas, and collaborate towards shared goals—focusing on survival and well-being. Emphasising collective effort, cooperation, and mutual respect instead of European competition, exploitation, or formalism, might just be the way forward. Let our radical imagination inspire us to rethink our actions and reshape the ongoing struggles of today and tomorrow. Fadia Faizy shares her journey and reminds us of the importance of approaching situations like forced migration with humility, rather than as saviours.

The Escape

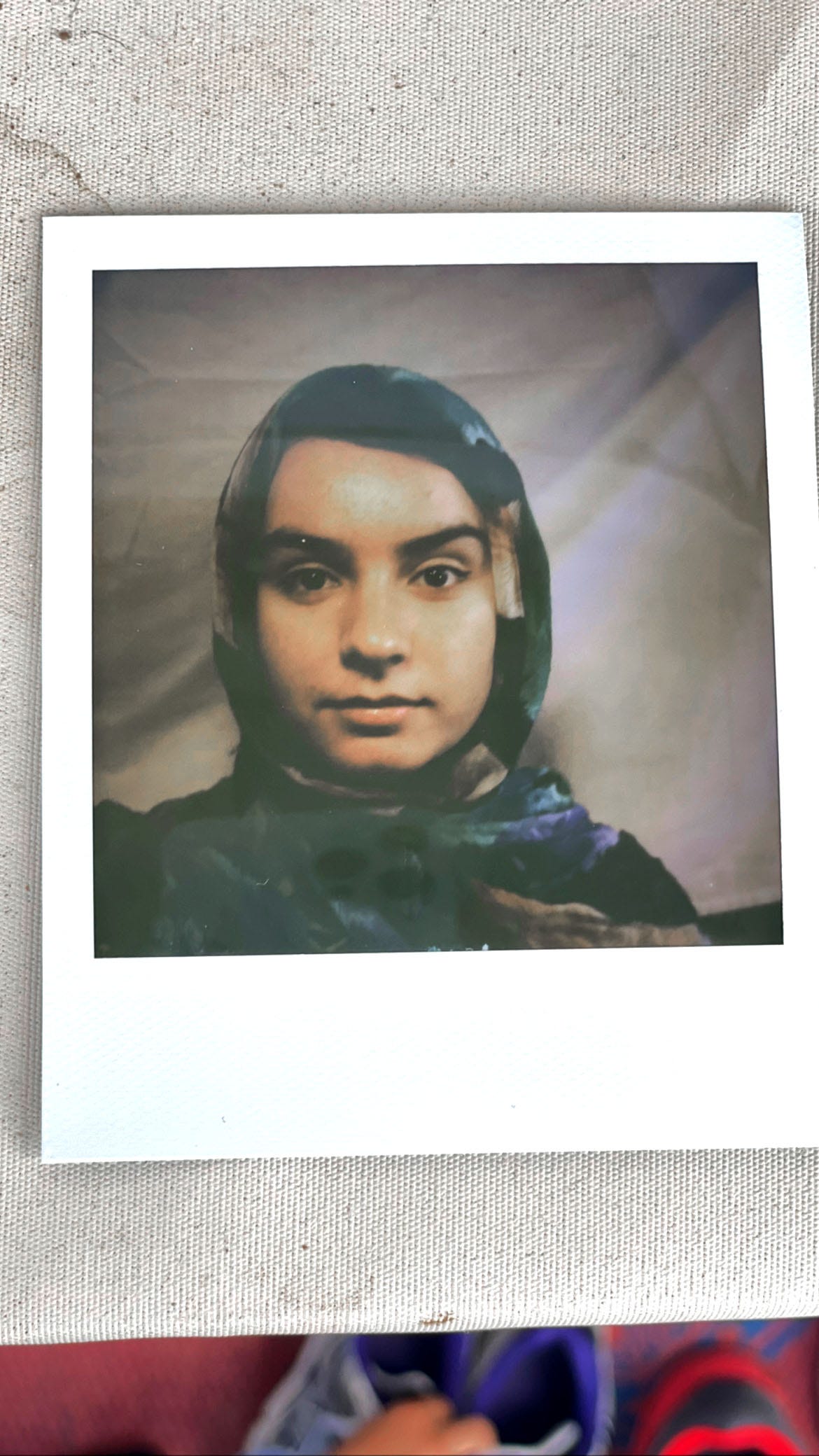

Fadia Faizy (Fig. 1) was 16 years old when we met her. Born in Herat, Afghanistan, she was studying to become a midwife and preparing to enter university. It was then that the Taliban army took control of her city, and she had to flee with her entire family. They first crossed into Iranian territory before reaching the border with Turkey, their initial destination in Europe. From there, they embarked on a boat journey in an attempt to reach Italy by sea. In the Mediterranean, without petrol, they asked the Greek maritime police for assistance, but were refused. Adrift, out of nowhere, a Filipino merchant ship appeared, rescued them, and took them to a port in Greece.

“Our boat was small, and the Philippine vessel was enormous. It was listing, and our boat was rocking, making it difficult to reach the larger boat. So, we had to leap out and jump from the small boat to the bigger one. When we jumped, people on the Philippine boat tried to grab our hands. Some of the crew fell into the water, and the sea silenced their voices.”

Upon arriving in Greece, the police denied them asylum; they were swiftly returned to Turkey and spent two days in the forest, between two rivers, at the border separating both countries. In their desperation, and unable to swim, they built a raft from branches and crossed the river to reach Greece, where, upon being detained, they were placed in the Malakasa Refugee Camp, 70 kilometres from Athens. Once in the camp, they can no longer be deported legally, and within one to three years, they will receive new documentation.

Her situation, like that of any refugee in Greece, is critical. Thousands of people are trapped inside the country, far from the cities, living in refugee camps. In deplorable conditions and with few opportunities to obtain international protection, the accommodation centres are overcrowded and not suitable for long-term stays. The asylum process is complicated due to a lack of resources in a system already in crisis. The European Union has focused its aid on the agreement with Turkey, neglecting the refugees trapped in Greece. By not implementing the relocation programme and closing the Balkan route, hundreds of migrants remain stuck for years in a bureaucratic maze.

Autonomy and radical imagination

In the documentary “Our Voices” (2020), Fadia shared her escape with us during an interview conducted in the refugee camp. During the interview, a strong emotional bond was formed. After several informal conversations, we agreed to continue collaborating in the following months because she wanted to maintain the project and thus continue communicating the situation of the refugee camp. She was seeking tools for peaceful struggle for her rights. Thanks to her, we opened ourselves to the idea of a possible production of knowledge, emphasising the area that emerges among people in a relational manner, through affection. We wanted to be part of a process in which it would be unlikely to have control, with the willingness to cooperate, but to disappear as designers, as authors and narrators of a story we have not lived.

Three months later, in March 2021, we began a series of online sessions with Fadia with the aims of supporting the creation of protest tools and activating local knowledge in the service of speculation about other worlds and their possibilities through the tools of design and communication.

She organised a series of workshops with young people and children from the countryside (Fig. 2), creating a network of affections that later allowed her to approach the community to explain the possibility of collaborating and carrying out protest actions in Athens regarding the emergency situation of other migrants who could not cross the border between Turkey and Greece (Fig. 3). It was about helping family and friends who remained blocked in the forests, exposed to the elements for weeks, losing their lives due to the extreme winter temperatures.

Through her workshops, Fadia realised that, for her message to resonate, it needed to be short, clear, precise, and understandable. She immersed herself in the task of creating protest messages that could be easily understood and shared by everyone. It was about communicating the demands and needs of her community effectively. Together with the participants, she designed protest posters and banners (Fig. 4, 5). But her proposal did not stop at merely creating protest tools.

Under the slogan “Open the borders” (Fig. 6), she designed a series of guerrilla tactics that culminated in a demonstration in the city of Athens through his non-violent protest (Fig. 7, 8), demonstrating that the sum of many small parts can dream of ending power structures (Hasak-Lowy, 2020).

In the process of weaving community that Fadia carried out intuitively and informally, strategies based on networks of affection emerged as a destabilising way of challenging the system, where power became the capacity to do something. Her practice, her makeup workshops, first, the creation of protest posters and banners, then, and the demonstration in Athens, became a set of collective knowledge that invited us to question our certainties, establishing unsettling dialogues through the differences between guiding processes and letting them flow freely, without the hand of the expert aesthetician. Living in border zones produces knowledge by being within a system and, at the same time, retaining the knowledge of a stranger coming from outside the system (Anzaldúa, 2012).

Fadia and her community’s critical discourse about their reality becomes a way of re-creating it. The development of their own language announced that the world they aspired to was being created in their imagination, using language as a path to invent citizenship (Freire, 2022). Design, transformed into a lever of invisible action and disciplinary disobedience, shifted towards more collective approaches, accompanied by gestures, processes, and dialogues. In this way, the revolutionary virtue consisted, in a community gesture of survival, of coexisting with those who are different in order to fight against those who are antagonistic.

Errors and lessons learned

It is here where we find one of the learnings: autonomous design turns out to be a praxis with communities that aims to contribute to their realisation as the type of entities they are (Escobar, 2018a). Thus, the community practices for itself: its organisations, its social relations, and its practices are independent of expert knowledge, of the designer. The people are practitioners of their own knowledge. The community designs under a self-learning system.

The second lesson is that, no matter how much we want to cooperate, it is the communities in emergencies that, in practice, find their own autonomous spaces, tools, and resources for cooperation and survival. The example of Fadia, her community, and the use of her radical imagination make us reconsider what we should do, how we should avoid intervening in their processes, and how their interests diverge from our simple interest in participating in issues that surpass us. Operating from a distance, from those who do not live what they experience, helps us question our role and positions us in our original stance — that of grateful learners, learning to let others think and act.

Fadia now lives in Germany, where she has built a new life and is actively participating in her community. She is an active member of ROSA, a non-profit organisation that aims to think with gender sensitivity about humanitarian aid and to provide safer spaces for women in situations of escape. In October 2022, the first local ROSA groups were established in Germany to actively promote safe escape routes for all genders. Additionally, the Rolling Safespace is located on the Attica Peninsula in Greece, where three shelters north of Athens receive regular visits throughout the year, including Malakasa. In 2023 alone, ROSA provided a safer space at the EU’s external border for more than 5,000 women.

Bibliographical references

Anzaldúa, G. E. (2012). Now let us shift… the path of Knowledge… inner work, public acts1. In This Bridge We Call Home (pp. 540-578). Routledge.

Escobar, A. (2018a). Autonomous design and the emergent transnational critical design studies field. Strategic Design Research Journal, 11(2), 139–146.

Freire, P. (2022). Pedagogía de la esperanza. CLAVE INTELECTUAL.

Hasak-Lowy, T. (2020). We are power: how nonviolent activism changes the world—Abrams Books for Young Readers.